This story was supported in part by a grant from the Pulitzer Center and is co-published in partnership with The Diplomat.

A confidential contract between tobacco giant Imperial Brands and Laos has delivered millions of dollars to a relative of the impoverished Southeast Asian country’s former leader, documents obtained by The Examination show.

Signed behind closed doors in 2001, the contract includes a 25-year tax freeze that has kept cigarette prices among the lowest in the world while smoking rates in the communist nation have remained among the highest in the region.

Cigarettes from Imperial’s Laotian joint venture sell for the equivalent of 32 cents a pack — less than a can of Coke or a candy bar — in a country where smoking-related diseases account for 1 in 7 deaths. Research shows that raising cigarette taxes is among the most effective ways to reduce smoking, particularly among children.

The revelation of the contract’s ramifications comes at a pivotal time: It is set to expire next year, and Laos’ current prime minister, Sonexay Siphandone, said in November that the government would not renew it. It’s unclear what a new agreement with Imperial or another manufacturer might look like.

The Laos contract points to a larger pattern of major tobacco companies striking opaque deals with cash-strapped authoritarian governments that benefit insiders and keep cigarettes cheap and accessible.

That long-standing pattern includes international companies facing charges for violating sanctions on North Korea, allegations of supplying cigarettes to jihadist groups in Mali and accusations of paying bribes to African delegates to an international anti-tobacco conference. In Egypt, Philip Morris International and a politically connected partner recently took a major stake in the military government’s cigarette monopoly through a series of obscured transactions, The Examination reported last year.

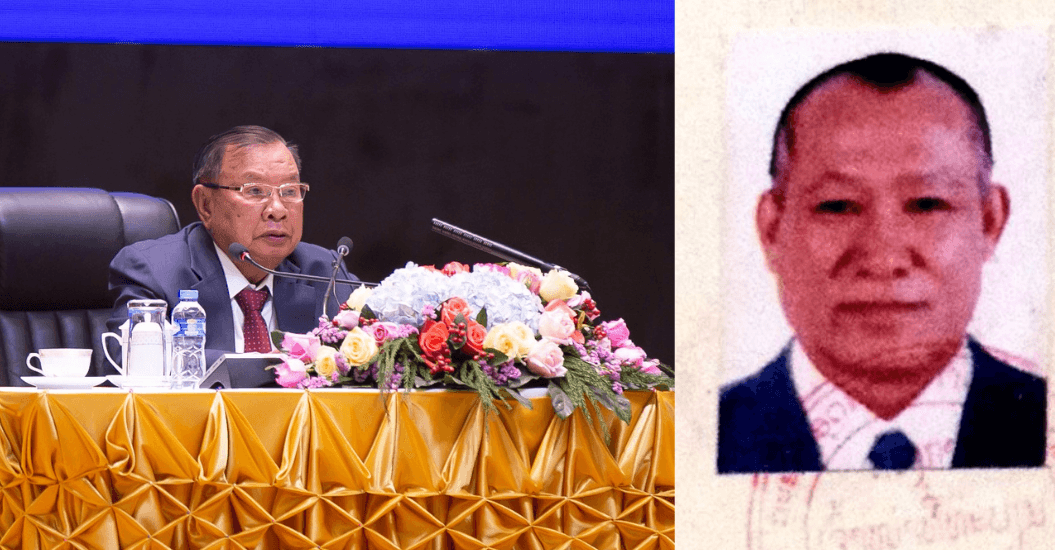

In Laos, the arrangement between U.K.-based Imperial, the country’s then-prime minister, Bounnhang Vorachit, and his in-law, business tycoon Sithat Xaysoulivong (their children are married), deprived the government of more than $140 million in tax revenue, according to one study from a tobacco control group. Part of that money would have been earmarked for tobacco control.

The pact privatized Laos’ state tobacco monopoly by creating a joint venture between the government and Imperial, the world’s No. 5 cigarette maker. As part of the deal, a holding company, partly owned by one of Sithat’s companies, received a minority stake in the venture.

“This has all the hallmarks of a corrupt scheme,” said Kush Amin, a legal specialist at the anti-corruption group Transparency International, who reviewed the documents obtained by The Examination.

When an ally and family member of a senior official receives shares in a joint venture and the corporate partner benefits from preferential tax treatment as part of the deal, “it only raises questions for a publicly traded company like Imperial,” Amin said.

Imperial is “committed to operating with integrity and in adherence with all applicable compliance standards,” the Bristol, England-based company told The Examination in a written statement.

The investment agreement came at a time when Laos’ tobacco monopoly “faced significant financial and operational challenges” and the multinational “brought the capital and expertise needed to stabilise and modernise the business, generating substantial dividend and tax revenues for the government,” it said.

As part of the arrangement, the Laotian government is barred from disclosing terms of the deal without Imperial’s permission. “There will be no release or making known to the public of this Agreement and amendments or any thing related to this Agreement” without the unanimous consent of the parties, the contract says.

Imperial said the contract’s confidentiality is “standard for commercial arrangements of this nature.” The company did not address detailed questions about the transaction and its relationship to the former president’s in-law.

While previous news stories have revealed several details of the contract, including the tax caps, The Examination’s reporting exposes for the first time the financial arrangement that has delivered millions to a relative of the former prime minister.

Neither Sithat nor Bounnhang responded to detailed questions sent to them for this story.

‘Most favoured company’

The agreement between the Laotian government and Imperial created a tobacco company called Lao Tobacco Ltd. that offered an array of business advantages. It gave the government 47% of the new joint venture. An additional 34% was held by an Imperial subsidiary, Coralma International. The remaining shares went to a newly created Singapore-based company named S3T Pte., co-owned by Imperial and Sithat’s Laotian conglomerate, ST Group.

Under the terms of the documents obtained by The Examination, Sithat would pay $990,000 for a stake in the venture. Those shares have generated more than $28 million in dividends through 2023, according to financial records obtained by The Examination.

The holding company exists to hold shares and distribute tobacco profits. In an affidavit filed in an unrelated New York court case, Sithat said S3T “has no other business operations.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Global health reporting, straight to your inbox

Imperial, which controls about two-thirds of the cigarette market in Laos, does not publicly disclose how much it makes in the country, and the government does not release the joint venture’s annual financial statements. However, calculations by The Examination based on S3T’s financial records indicate Imperial earned about $145 million in dividends from its Laos operations over two decades, from an initial investment of $4.6 million.

Terms of the deal granted the new company and its investors preferential treatment. Among a host of incentives, the government agreed to waive taxes on both income and foreign-paid dividends for five years and to cut tariffs on imports of raw materials. Lao Tobacco also received “most favoured company” status in Laos, guaranteeing the government could not offer future competitors better incentives.

Most significantly, the agreement capped excise taxes, leaving Laos with some of the world’s cheapest cigarettes.

Taxes on Laos’ most popular brand of cigarettes were just 12% of the retail price, according to a 2021 World Health Organization study. That’s a fraction of the 75% minimum recommended by the WHO or the 79% tax in neighboring Thailand.

A tax increase that raises the price of cigarettes by 10% cuts consumption by 5% on average in lower- and middle-income countries, according to the WHO.

The trade-offs for inexpensive tobacco have been substantial. As in many Asian nations, few Laotian women smoke. But at 37%, the country’s male cigarette smoking rate is among the highest in the world, according to WHO estimates.

Laos’ lawmakers have approved tobacco tax increases on three occasions since 2015 — only to have Imperial’s joint venture refuse to comply, citing the 2001 contract. The contract cost the government $143 million in lost tax revenue through 2019, according to calculations by the Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance.

“The Lao people have already suffered from this contract for 25 years,” said Bungon Ritthiphakdee, executive director of the Thailand-based Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control. “The question is whether a new generation will have to continue suffering.”

In his 2023 memoir, Sithat hailed the deal as “a model for joint investment” and touted the modernization of Lao Tobacco’s facilities and the economic benefits to farmers. He highlighted the fivefold increase in the number of families supported by growing tobacco and said the venture was in line with the communist government’s aim “to gradually lift people out of poverty.”

‘Everyone can buy cigarettes’

The toll cheap cigarettes have taken is evident in the pulmonology ward at Mahosot Hospital, a government facility near the banks of the Mekong River in the capital, Vientiane.

There, a half-liter of milky pink liquid has collected inside a bottle connected to a tube that is draining the left lung of a rice farmer named Jonh. The 20-year-old was brought to the hospital from a village five hours northwest of the city after he began having chest pains and difficulty breathing. He lies wheezing in a hospital bed.

The diagnosis: pleural effusion, a buildup of fluid in the tissues around the lung, and empyema, an accumulation of pus in the same area that is often caused by pneumonia.

Damage to his lungs from the pack a day of Lao Tobacco’s Bastos cigarettes he smokes likely made him more vulnerable to respiratory infections, according to Jonh’s doctor, a 61-year-old pulmonary specialist named Sisouphanh Vidhamaly.

“I am not sure if he will recover … we need to kill the bacteria,” Sisouphanh said. “I advised him to stop smoking, but once he leaves the hospital, I don’t know if the patient is going to stop or not.”

Sisouphanh bustles about her ward with a wide smile and dressed in a traditional silk skirt. She has spent much of her career treating smoking-related diseases such as lung cancer, pneumonia and bronchitis and says respiratory ailments are on the rise in Laos.

“Everyone can buy cigarettes these days. They are easily accessible,” she said. “Kids go to the corner shop to buy for their parents and it is considered normal.”

Patients like Jonh are hardly unusual. “If the cost of cigarettes were higher, it would help to reduce the rate of smoking since a higher price means a higher barrier to entry for young people in particular,” Sisouphanh told The Examination.

Jonh’s mother, Daone, worries for him and for the family’s finances, which are under strain on his fourth day in the hospital. The stay will cost about 19 million kip (roughly $875). In a country where per capita income is $2,100 per year, she may be paying the hospital debt for months. A nurse, concerned that Jonh will be discharged early because his family can’t afford his stay, is teaching Daone how to drain Jonh’s lungs herself.

Low-cost cigarettes have lured smokers like 22-year-old Anouluk, a construction worker in Vientiane. As a child, he grew up fetching cigarettes from the store for his heavy-smoking father. Eventually, Anouluk too began smoking — pretending to buy the cigarettes for his dad and then keeping them for himself.

He started with friends during lunch breaks at school or in the restroom after dodging class. Before long, Anouluk, whose last name is withheld for security reasons, was smoking as much as a pack and a half a day.

With monthly earnings of 2.5 million kip, (about $115) he doesn’t always have money to buy his own smokes and sometimes gets Lao Tobacco’s Red A cigarettes from others — or receives free cigarettes from his employer as a perk.

But Anouluk’s views on smoking changed after an X-ray showed his father had lost half his lung capacity. That spurred Anouluk to try to cut down to four or five cigarettes a day.

“I know I am addicted,” he said. “I would be able to quit if I was not.”

The ‘top millionaire’ in Laos

In his memoir, the 77-year-old Sithat refers to himself as “the top millionaire in Laos” and says he dreams of being the first Laotian in space. The son of Chinese immigrants whose father died when he was 10, Sithat never graduated from high school and got his start as a schoolboy selling rice whiskey by boat on the Mekong River.

In 1978, he moved to the provincial capital of Savannakhet, where his path would meet that of Bounnhang, an officer and veteran of the communist insurgency that had recently toppled the country’s U.S.-backed royalist government.

Bounnhang would become regional governor, and after flooding devastated Savannakhet, he asked the young businessman for assistance. Sithat responded by giving $50,000 to help the government address rice shortages, according to his memoir.

In return, Bounnhang’s provincial government gave Sithat logging rights to valuable stands of Siamese rosewood. This allowed Sithat, who had no experience in logging, to enter Laos’ “very profitable” wood export business, he wrote. Within three years, Sithat had made $2 million.

Sithat credited his decision to help Bounnhang with advancing his business career. “Maybe because of this work, I have gained special trust from the top,” he wrote in his memoir.

In the early 1990s, both men moved to Vientiane, where Bounnhang had been named mayor and would rise to the ruling party’s Politburo. During this time, Laos was opening to private enterprise and Sithat was granted permission to launch the country’s first duty-free store near a new bridge to Thailand — a store that would earn as much as $30,000 per day. Sithat’s growing ST Group, went on to launch a road construction company and a wine cooler distributorship.

The two men’s ties were deepened by the marriage of Bounnhang’s son Toulaxay to Sithat’s daughter Deuandala in the late 1990s.

“The relationship between Sithat and Bounnhang, including the marriage between their children and the mutual support — financially and through the use of political power — is well known among people in Laos’s upper circles,” said Joseph Akaravong, a Laotian political activist who fled the country in 2018 after criticizing the construction of a dam that later collapsed, killing dozens.

The growing alliance between the two men came just as Imperial had begun seeking international acquisitions that would transform it from a U.K.-focused company to the global tobacco giant it is today.

After acquisitions in Western Europe and Australia, Imperial began pursuing investments in Southeast Asia, including Laos.

Laos remains an economy and a polity where success only happens when you know the right senior people in and around the Communist Party.

Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations

In 1999, Bounnhang was promoted to finance minister. The following year, as Imperial negotiated the purchase of Coralma — a French tobacco company with operations in neighboring Vietnam — company executives were invited to make a proposal with Sithat’s ST Group for Laos’ state tobacco monopoly, according to a copy of the joint venture agreement.

Bounnhang became prime minister in March 2001, and eight months later the privatization was finalized.

“Laos remains an economy and a polity where success only happens when you know the right senior people in and around the Communist Party,” said Joshua Kurlantzick, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who researches Southeast Asia. “He [Sithat] is one of those right people.”

‘Red flags’ for bribery investigation

For Imperial, signing a similar contract today might prompt a legal inquiry in the U.K., said Amin, the Transparency International legal specialist.

“There are a number of red flags on this 2001 Imperial Tobacco deal which would have justified a serious law enforcement investigation” had the U.K.’s Bribery Act of 2010 been in effect when it was signed, he said.

That law, which is similar to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, allows the British government to pursue bribery investigations overseas as long as the company in question does business in the U.K. The law holds a company liable for failing to prevent anyone associated with it from paying bribes to benefit the company.

Sithat’s lack of experience in the tobacco sector and familial relationship with the prime minister whose government awarded the contract is “suspicious” but not the only warning sign on the deal, Amin said. There is also “little justification” for Imperial to own 34% of the Laotian venture directly while also holding another stake in a company it jointly owns with a politically-connected businessman, he added.

“That both Imperial and Sithat have continued to receive tens of millions of dollars in dividends from the same deal up to 2023 raises serious questions as to whether these payments continue to influence their ability to do business in Laos,” Amin said.

Imperial Brands did not answer questions about the motivation behind the arrangement and said it could not comment on details of the contract.

Bounnhang, now 87, lives in Vientiane.After serving as prime minister until 2006, he became vice president and then president of Laos before stepping down in 2021. Politics in the country are often dynastic, and his daughter Bounkham is now the country’s minister of environment and natural resources.

As for Sithat, the 2001 tobacco agreement was just the start of a period of rapid growth and diversification for his family’s businesses, which often included roles for his children. Documents name his son-in-law — Bounnhang’s son Toulaxay — as being involved in a mining enterprise co-owned by Sithat’s family.

Sithat became a key local associate for foreign companies looking to do business in Laos, partnering with a Thai dam-building firm and an Australian mining company, among other projects. Over the years, he founded a bank, built hotels and launched ventures in cosmetics and casinos.

“He’s joined at the hip with Bounnhang,” a former partner of Sithat, said he was told by a top Laotian official, according to a filing in a legal dispute between the two businessmen.

It’s very critical for the Lao government to decide whether they want to continue giving preferential treatment to an industry whose products make people sick.

Bungon Ritthiphakdee, executive director of the Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control

Prosperity for the country

The decision of what happens next is ultimately up to Prime Minister Sonexay.

Giving a tobacco giant similar tax breaks would violate a global treaty on tobacco control that Laos joined in 2006.

“It’s very critical for the Lao government to decide whether they want to continue giving preferential treatment to an industry whose products make people sick,” said Bungon, of the Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control.

The secretariat of the Laotian parliament sent Sonexay’s office a letter late last year urging the government to “investigate and impose penalties” over Imperial’s deal that “resulted in significant losses to national revenue and negatively impacted the health of the Lao people.”

Several days later, the government sent a notice to Imperial terminating the contract. It did not reference any investigation and left open the possibility that a new contract between Laos and Imperial might be negotiated. If Imperial’s subsidiary “would like to continue the tobacco business, [Lao Tobacco Limited] should ask the permission from related Ministries,” it said.

In Sithat’s memoir, a photo of him and Bounnhang sitting side by side on a couch is included on the next-to-last page.

“Some people complain about me or say that some of my businesses operate in the gray,” Sithat wrote. “I can confirm that every business of mine is under the law of the nation and helps to bring growth to the nation.”

Directly above that picture is a formal photo of him with another major political figure: Laos’ president from 1998 to 2006, the father of today’s prime minister, Sonexay.

The Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control and the Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance have received support from Bloomberg Philanthropies, which also provides financial support to The Examination. The Examination operates independently and is solely responsible for its content.